teaching philosophy

The essence of my teaching philosophy and style derive from my personal answers to five fundamental questions:

- What is the ultimate goal of medical training?

- Which of these goals can a teacher or mentor influence?

- How do students learn?

- How should we evaluate students?

- Who should evaluate students?

What is the ultimate goal of medical training?

The goal of medical training is to produce good clinicians. What makes for a good clinicians?

The tools of the good clinician are many, and include a solid database of scientific and clinical knowledge, problem solving skills, physical exam skills, and communication skills. However, these are but the means through which clinicians pursue their task. Their mastery is a necessary but insufficient step in the process of becoming a complete physician.

There are higher level skills and traits that help to distinguish those who technically could provide good care for their patients, and those that do. These vary to some degree amongst clinicians, but for me, the key attributes are work ethic, intellectual curiosity, resourcefulness, accountability, respect, honesty, and caring.

These are not the types of traits that can be turned on or off, but rather are mostly working methods and personality traits that have been fostered through role modeling, introspection, and hard work. I believe this is what Aristotle must have had in mind when he said that “Quality is not as act, it is a habit”, and I believe this is what many people mean when they speak about professionalism (although that term has unfortunately been hijacked by guilds and trade associations such that its noble connotations are now obscured and diluted).

Good clinicians possess specialized knowledge and special skills, but more importantly their actions are guided by internalized values, traits, and working methods that are the backbone of the profession. Passing on this legacy is the ultimate goal of medical training.

Which of these goals can a teacher or mentor influence?

Unfortunately, most teachers exert relatively little influence on most students. This, for a variety of reasons – amongst others, the limited contact between staff and students, and the fast pace of clinical life. Teachers can impart tidbits of information, but learning only occurs if the information falls on fertile soil. In most cases, those who are most inclined to learn, are in least need of the teaching. By and large, I do not believe that teachers teach students, nor that patients teach students. Students, who are motivated to learn, teach themselves and they will use whatever clinical material and other resources at their disposal to do so.

The teachers I remember most are not those who had the most encyclopedic knowledge (although some of them did), but rather those who embody a love of learning, or of their profession, or of caring for their patients. For better or for worse, we are role models for our students, and our greatest influence lies more than anything else, in the core values that we express in our daily work.

How do students learn?

We live in a society that recognizes the value and necessity of lifelong learning. Yet some people are better learners than others. To understand why, we must try to understand how people learn.

We live in a society that recognizes the value and necessity of lifelong learning. Yet some people are better learners than others. To understand why, we must try to understand how people learn.

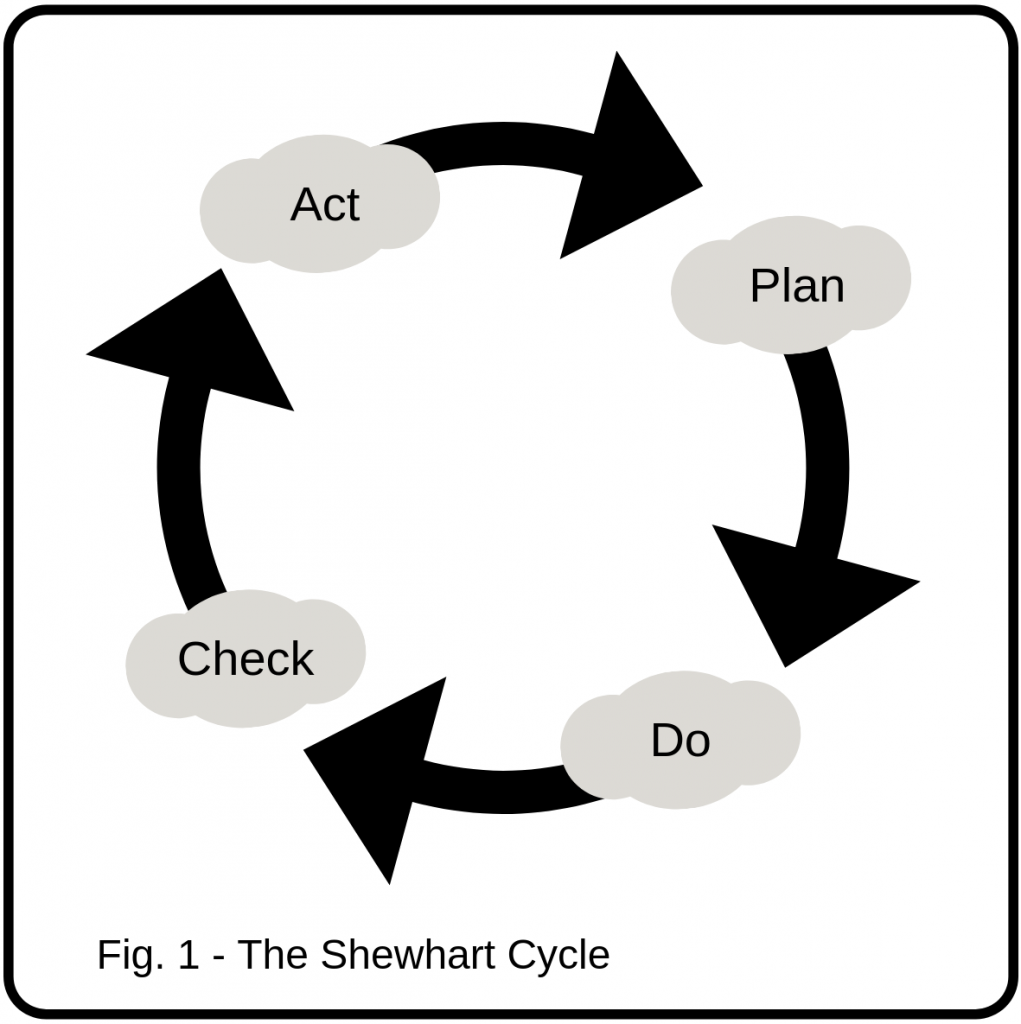

Walter Shewhart was a statistician, who in the early 19th century gave rise to the methodologies that have become the cornerstone of modern industrial quality control. His concepts today have wide ranging applications including their use in faculty assessment and development in educational institutions. The core of Shewhart ́s teachings are the notion that for learning to occur there must be continuous and reiterative evaluation and modification (see Fig. 1). These concepts seem obvious today, and variants of Shewhart’s cycles can be found in almost any field.

Shewhart’s principles are particularly relevant to the practice of medicine. Medicine is highly repetitive, and this model applies both to the ongoing learning associated with accumulated case exposure, as well to the reiterative trial and error problem solving that may be used during the care and management of a single patient.

Effective lifelong learners intuitively understand this and they demonstrate the behavioural determinants of learners, which are flexibility, openness to criticism, the courage to make and admit mistakes, and the desire to improve. This insight, coupled with access to credible sources of external evaluation are the cornerstones of learning, and students who possess both, progress incrementally and surely towards mastery in their profession.

How should we evaluate students?

There is a collegial bond between physicians and their trainees; and a social contract between them and the society. Young physicians will grow up to care for our patients, and probably for us. It is in our own self-interest to take this task seriously.

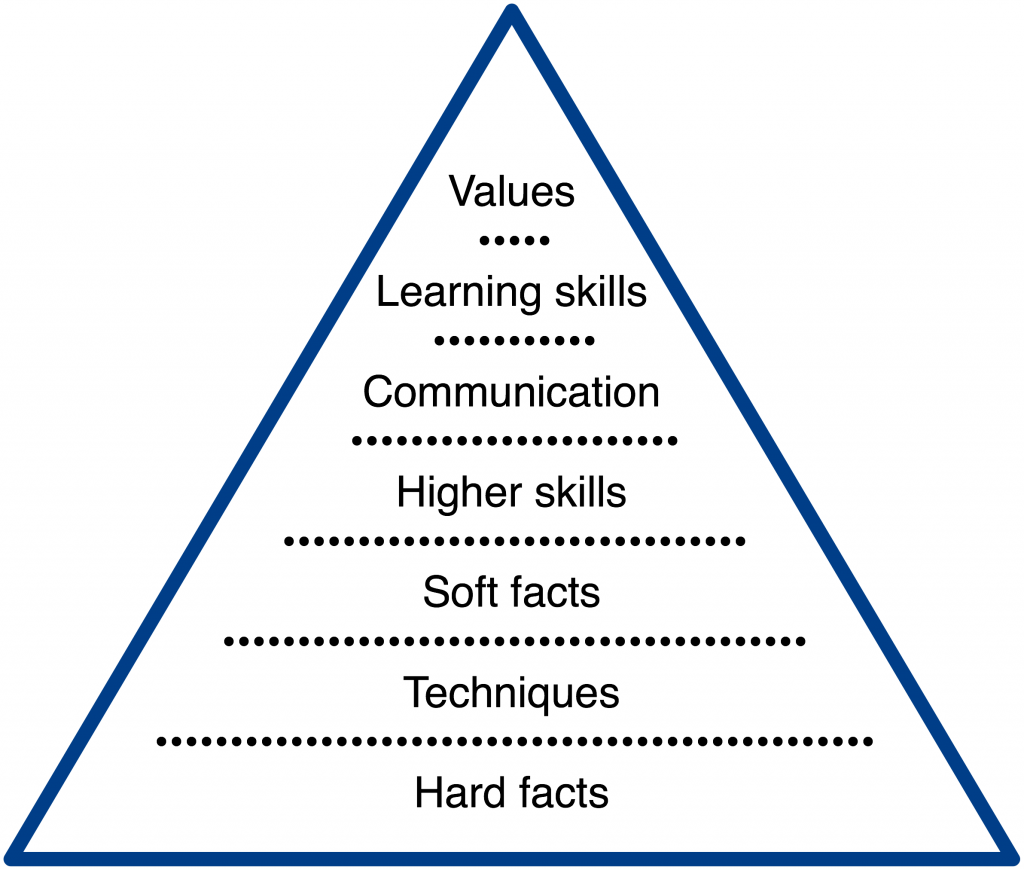

As we have seen, there is much to be learned during the training period. What should be the focus of clinical evaluation? There are a variety of skills and values that are subject to analysis. The skills and values that I focus on are listed below with some examples:

Hard facts

- The heart is a four chambered organ that pumps blood throughout the body.

- The AV node normally becomes increasingly resistant to conduction as heart rate increases.

- Hypoxic vasoconstriction is an adaptive phenemon that promotes V/Q equilibrium.

Skills

- Central line insertion

- Bedside examination, etc.

- Calculation of an Odds Ratio

Soft facts, and judgment

- Ability to identify a sick patient

- Prioritization of problem lists

Higher skills

- Critical thinking

- Synthesis

- Problem solving

Communication

- Verbal and written case presentation

- Discussion with patients and families

Learning skills

- Insight, humility, openness to criticism

Values

- Life-long learning.

- Caring, compassion and respect for patients and colleagues

Traditionally, these skills are approached as steps in the training of clinicians that build on each other (see Fig 2). Clearly, skill acquisition can be synergetic (e.g. improving knowledge may improve judgment, communication or problem solving), but I believe that the order in which trainees acquire various skills varies amongst individuals; and that not all skills and attitudes contribute equally to clinical performance.

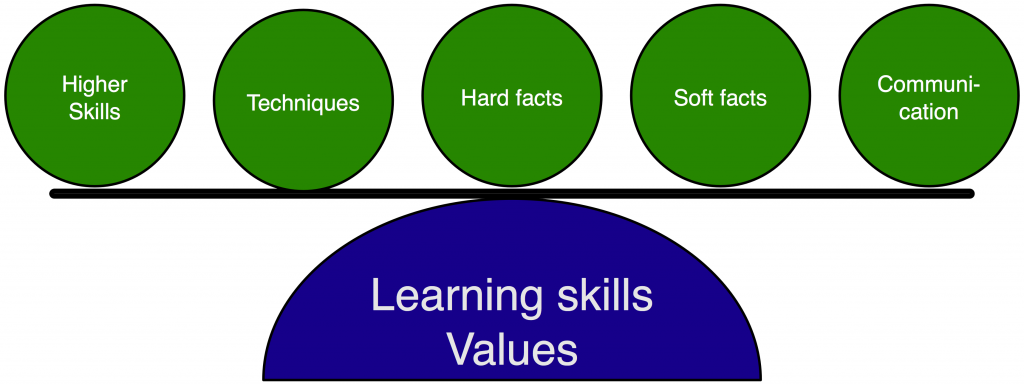

In contrast to the above model, I believe that the foundation of training rests on the core values of the profession, and on the development of learning habits and aptitudes. Upon this base, a balanced set of clinical skills completes a clinician’s training (see Fig. 3)

The evaluation of these skills is complicated by the fact that they are not performed in isolation, rather they are intertwined and buried in the process we call clinical care. The challenging and rewarding task of the teacher is to dissect the signal from the noise, and identify which skills in the hierarchy are being performed, and which are not. This is furthered obscured by patient outcomes (many patients do well no matter how they are treated), and the bias of personality, and individual style (teachers must learn to distinguish between issues of preference and issues of performance).

Thus, evaluation can be a time consuming, and daunting task. Not all situations lend themselves to a comprehensive evaluation of all skills. Circumstances and the discretion of the teacher should determine the level of any individual evaluation. Independent of these choices, it is clear that the evaluation of students is one of the most critical acts that a physician can do. It is our duty to perform this task with rigor, compassion, and honesty. The focus of my teaching in my community setting, is seven fold:

- To expose trainees to a practice pattern of community GIM that they might not see within a metropolitan area.

- To confirm that a modicum of medical knowledge and skill has been acquired, or to document it when such knowledge and skill is lacking.

- To evaluate trainee’s levels of judgment, critical thinking, and communication skills.

- To evaluate trainee’s learning skills.

- To provide honest feedback to residents highlighting their strengths and especially their weaknesses in the above mentioned areas.

- To promote the acquisition of ethical practice patterns and professionalism, and

- To motivate trainees to be their best.

Who should evaluate students?

For over a decade I have realized the limitations of my first person perspective as the judge of a candidates competency and performance. It is evident that medicine is a team sport and it behooves us to harness the collective wisdom of the team in our evaluations. To that end, I have developed and implemented a multi source feedback tool that I routinely apply to trainees. This is discussed in greater detail in the assessment section.